(cont.)

Musicanus

Musicanus (Ancient Greek: Μουσικανὸς,[35] Indian: Mûshika[citation needed]) was an Indian king at the head of the Indus, who raised a rebellion against Alexander the Great c. 323 BC. Peithon, one of Alexander's generals, managed to put down the revolt:

"Meantime he was informed that Musicanus had revolted. He dispatched the viceroy, Peithon, son of Agenor, with a sufficient army against him, while he himself marched against the cities which had been put under the rule of Musicanus. Some of these he razed to the ground, reducing the inhabitants to slavery; and into others he introduced garrisons and fortified the citadels. After accomplishing this, he returned to the camp and fleet. By this time Musicanus had been captured by Peithon, who was bringing him to Alexander." – Arrian Anabasis[36]

Porticanus

The King of Patala, Porticanus came to Alexander and surrendered. Alexander let him keep possession of his own dominions, with instructions to provide whatever was needed for the reception of the army.[35]

Sambus

Sambus was yet another ruler in lower Indus valley. According to Diodorus Siculus, Alexander invaded his kingdom, killing eighty thousand people and destroying cities. Most of population was taken into slavery, and Sambus himself ‘fled with thirty elephants into the country beyond the Indus’.

Revolt of Alexander's army

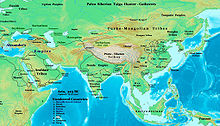

Asia in 323 BC, the Nanda Empire and neighboring Gangaridai of Ancient India in relation to Alexander's Empire and neighbors.

East of Porus's kingdom, near the Ganges River (the Hellenic version of the Indian name Ganga), was the powerful Nanda Empire of Magadha and the Gangaridai Empire of Bengal. Fearing the prospects of facing other powerful Indian armies and exhausted by years of campaigning, his army mutinied at the Hyphasis River (the modern Beas River), refusing to march further east.[37]

Alexander's troops beg to return home from India in plate 3 of 11 by Antonio Tempesta of Florence, 1608.

As for the Macedonians, however, their struggle with Porus blunted their courage and stayed their further advance into India. For having had all they could do to repulse an enemy who mustered only twenty thousand infantry and two thousand horse, they violently opposed Alexander when he insisted on crossing the river Ganges also, the width of which, as they learned, was thirty-two furlongs, its depth a hundred fathoms, while its banks on the further side were covered with multitudes of men-at-arms and horsemen and elephants. For they were told that the kings of the Ganderites and Praesii were awaiting them with eighty thousand horsemen, two hundred thousand footmen, eight thousand chariots, and six thousand fighting elephants.

Chandraketugarh in West Bengal, India is believed to be the capital of Gangaridai. The Gangaridai army, with its 4,000 elephant force, may have led to Alexander's retreat from India.[39]

Gangaridai, a nation which possesses a vast force of the largest-sized elephants. Owing to this, their country has never been conquered by any foreign king: for all other nations dread the overwhelming number and strength of these animals. Thus Alexander the Macedonian, after conquering all Asia, did not make war upon the Gangaridai, as he did on all others; for when he had arrived with all his troops at the river Ganges, he abandoned as hopeless an invasion of the Gangaridai when he learned that they possessed four thousand elephants well trained and equipped for war.

Alexander, using the incorrect maps of the Greeks, thought that the world ended a mere 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) away, at the edge of India. He therefore spoke to his army and tried to persuade them to march further into India, but Coenus pleaded with him to change his mind and return, saying the men "longed to again see their parents, their wives and children, their homeland". Alexander, seeing the unwillingness of his men, agreed and turned back.

Mallian campaign

Main article: Mallian Campaign

Along the way, his army conquered the Malli clans (in modern-day Multan). During a siege, Alexander jumped into the fortified city with only two of his bodyguards and was wounded seriously by a Mallian arrow.[31] His forces, believing their king dead, took the citadel and unleashed their fury on the Malli who had taken refuge within it, perpetrating a massacre, sparing no man, woman or child.[41] However, due to the efforts of his surgeon, Kritodemos of Kos, Alexander survived the injury.[42] Following this, the surviving Malli surrendered to Alexander's forces, thereby his beleaguered army moved on and conquered more Indian tribes along the way.

Aftermath

Ptolemy coin with Alexander wearing an elephant scalp, symbol of his conquests in southern Asia.

The army crosses the Gedrosian Desert, by Andre Castaigne (1898–1899).

Alexander sent much of his army to Carmania (modern southern Iran) with his general Craterus, and commissioned a fleet to explore the Persian Gulf shore under his admiral Nearchus while he led the rest of his forces back to Persia by the southern route through the Gedrosian Desert (now part of southern Iran) and Makran (now part of Pakistan). In crossing the desert, Alexander's army took enormous casualties from hunger and thirst, but fought no human enemy. They encountered the "Fish Eaters", or Ichthyophagi, primitive people who lived on the Makran coast of the Arabian Sea, who had matted hair, no fire, no metal, no clothes, lived in huts made of whale bones, and ate raw seafood obtained by beachcombing.[43] During the crossing, Alexander refused as much water as possible, to share the sufferings of his men and to boost the morale of the army.[44]

In the territory of the Indus, Alexander nominated his officer Peithon as a satrap, a position he would hold for the next ten years until 316 BC, and in the Punjab he left Eudemus in charge of the army, at the side of the satrap Porus and Taxiles. Eudemus became ruler of a part of the Punjab after their death. Both rulers returned to the West in 316 BC with their armies. In c. 322 BC BC, Chandragupta Maurya of Magadha founded the Maurya Empire in India and conquered the Macedonian satrapies during the Seleucid–Mauryan war (305–303 BC).[45]

References

Citations

^ Fuller, p. 198

While the battle raged, Craterus forced his way over the Haranpur ford. When he saw that Alexander was winning a brilliant victory he pressed on and, as his men were fresh, took over the pursuit.

^ The Anabasis of Alexander/Book V/Chapter XVIII

^ Peter Connolly. Greece and Rome at War. Macdonald Phoebus Ltd, 1981, p. 66.

^ Bongard-Levin, G. (1979). A History of India. Moscow: Progress Publishers. p. 264.

^ The Anabasis of Alexander/Book V/Chapter XXVIII

^ Jump up to:a b R. K. Mookerji 1966, p. 3.

^ Jump up to:a b c Irfan Habib & Vivekanand Jha 2004, p. 1.

^ Jump up to:a b Irfan Habib & Vivekanand Jha 2004, pp. 1–2.

^ Irfan Habib & Vivekanand Jha 2004, pp. 2–3.

^ H. C. Raychaudhuri 1988, p. 32-33.

^ H. C. Raychaudhuri 1988, p. 33.

^ Jump up to:a b c Irfan Habib & Vivekanand Jha 2004, p. 2.

^ Jump up to:a b c Irfan Habib & Vivekanand Jha 2004, p. 3.

^ Jump up to:a b c Irfan Habib & Vivekanand Jha 2004, p. 4.

^ Irfan Habib & Vivekanand Jha 2004, pp. 3–4.

^ Jump up to:a b The Achaemenid Empire in South Asia and Recent Excavations in Akra in Northwest Pakistan Peter Magee, Cameron Petrie, Robert Knox, Farid Khan, Ken Thomas p.714

^ H. C. Raychaudhuri 1988, p. 46.

^ R. K. Mookerji 1966, p. 24.

^ R. K. Mookerji 1966, p. 25.

^ Ian Worthington 2003, p. 162.

^ Narain, A. K. (1965). Alexander the Great: Greece and Rome – 12. pp. 155–165.

^ "Quintus Curtius Rufus: Life of Alexander the Great". University of Chicago. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

^ Majumdar, R. C. (1971). Ancient India. p. 99.

^ Mukerjee, R. K. History and Culture of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, Foreign Invasion. p. 46.

^ Curtius in McCrindle, p. 192, J. W. McCrindle; History of Punjab, Vol I, 1997, p 229, Punjabi University, Patiala (editors): Fauja Singh, L. M. Joshi; Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p. 134, Kirpal Singh.

^ Robin Lane Fox 1973, p. 343.

^ H. C. Raychaudhuri 1988, p. 54.

^ Jump up to:a b c d Arrian (2004). Tania Gergel (ed.). The Brief Life and Towering Exploits of History's Greatest Conqueror as Told By His Original Biographers. Penguin Books. p. 120. ISBN 0-14-200140-6.

^ "Alexander the Great in India: Furthest and Final Conquests 327–325 BCE". 4 December 2021.

^ P.H.L. Eggermont, Alexander's campaign in Southern Punjab (1993).

^ Jump up to:a b Plutarch, Alexander. "Plutarch, Plutarch, Alexander (English).: Alexander (ed. Bernadotte Perrin)". Tufts University. Retrieved 30 May 2008. See also: "Alexander is wounded". Main Lesson. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

^ Rogers, p.200

^ Philostratus the Elder, Life of Apollonius of Tyana, § 2.12

^ Pande, G. C.; Pande, Govind Chandra (1990). Foundations of Indian Culture. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0712-9.

^ Paul J. Kosmin 2014, p. 34.

^ Plutarch, Alexander, 62

^ A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 189.

^ Megasthenes. Quoted from the Epitome of Megasthenes, Indika. (Diodorus II, 35–42), Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian. Translated and edited by J. W. McCrindle.

^ Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1967). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120800182.

^ "Ancient Surgery:Alexander the Great". Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

^ Arrian, Indica, 29

^ "Expansion of the Maurya Empire | Early World Civilizations".

Sources

A. B. Bosworth (1996). Alexander and the East. Clarendon. ISBN 978-0-19-158945-4.

H. C. Raychaudhuri (1988) [1967]. "India in the Age of the Nandas". In K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (ed.). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1.

Irfan Habib; Vivekanand Jha (2004). Mauryan India. A People's History of India. Aligarh Historians Society / Tulika Books. ISBN 978-81-85229-92-8.

Arrian (1976) [140s AD]. The Campaigns of Alexander. trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044253-7.

Ian Worthington (2004). Alexander the Great: Man And God. Pearson. ISBN 978-1-4058-0162-1.

Ian Worthington (2003). Alexander the Great. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29187-9.

Mary Renault (1979). The Nature of Alexander. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-73825-X.

Paul J. Kosmin (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

Peter Green (1992). Alexander of Macedon: 356–323 B.C. A Historical Biography. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07166-2.

Plutarch (2004). Life of Alexander. Modern Library. ISBN 0-8129-7133-7.

R. K. Mookerji (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0433-3.

Robin Lane Fox (1973). Alexander the Great. Allen Lane. ISBN 0-86007-707-1.

Robin Lane Fox (1980). The Search for Alexander. Little Brown & Co. Boston. ISBN 0-316-29108-0.

Ulrich Wilcken (1997) [1932]. Alexander the Great. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-00381-7.

Leave a Comment