Sell everything you own.

Sell your car, your home, and all your worldly possessions.

Then give the money to charity. And go live on a mountain.

Longing for inner peace, who hasn’t thought of doing this at some point?

Well, some have done it.

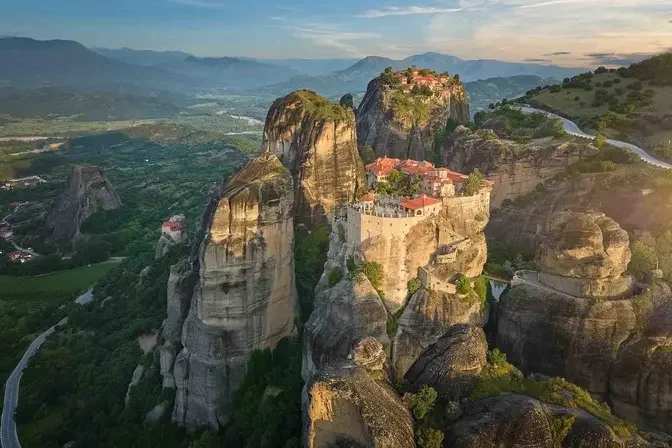

Evidence of ancient cave dwellings and twisted wooden ladders can still be found amid the towering, pillar-like formations just miles north of the town of Kalabaka. In some ways living that way must have been rough going; yet in other ways, it’s easy to grasp the appeal such a lifestyle had.

On one hand, the view from those cliffs overlooking the Pineios River valley was, and still is, perhaps, a religious experience itself—offering inspiration in their quest for divinity.

On the other hand, that which they were fleeing—a world beset with travails, political strife, and persecution—made life unlivable.

Eventually, this rather disorderly rabble of ascetics was gathered together and organized by a monk named Nilos. The monks here followed the Eastern Orthodox Church and would begin a lofty construction project amid the clouds.

It started with the Holy Monastery of Great Metéoron—the largest, built upon the grandest rock outcropping in the area—founded by the monk Saint Athanasios in 1344. The Holy Monastery of Varlaam, the second largest, was founded when the monk Varlaam managed to scale a peak where the Great Metéoron could be spied through the mountain mists.

Steps were carved directly into the living rock; although the journey was still treacherous and steep, often ascending over 1,500 feet, at least now it was passable for the able-bodied, courageous, or ardent pilgrim.

And scores of others cropped up, crowning the rock columns standing gallantly across the valley. Together, they became Metéora, translating from Greek as “suspended in air.”

A miracle itself, this unique geography was formed over millions of years as sedimentary rock deposits were laid, and later fragmented by earth movements that raised the seabed. Weathering carved away these remnants, creating formations that are very unique compared to similar ones elsewhere.

Here and there are the reminders of the roughness of life in those early years—even as handfuls of monks and nuns call Metéora home today. The monks who began the construction work raised winch towers that can still be seen. Ropes were used to pull up building materials, goods, and people. There were ladders that could be brought up in the event of invasion, making the dwellers impervious to attack.

The construction must have been slow going; they often built vertically to compensate for limited ground space. But the difficult work paid off: The Great Metéoron was enlarged thanks to the hermit Ioasaf, the son of a Greek-Serbian king, and wealth and prestige followed as pilgrims flocked in.

The rock formations were plagued by earthquakes and landslides that caused roads and buildings to crumble. Nor were the compounds spared from the ravages of war. The earthshaking bombs and vibrations from low-flying German planes took their toll during World War II.

Efforts were made to conserve the site later, however. Metéora underwent conservation in 1972, and became a UNESCO-protected heritage site in 1988. The monasteries had survived.

Throughout the centuries, Metéora has endured persecution, invasion, earthquakes, and war. Now, it faces a new kind of invasion.

In our modern age of entertainment and tourism, Metéora’s doors remain open, as in the past. It has played host to throngs of visitors—and even movie makers.

The 1981 James Bond spy film “For Your Eyes Only” starring Roger Moore was shot onsite at the Monastery of Holy Trinity, with permission from the Greek Ministry of Culture. Yet not all were happy with this.

Every summer, Metéora turns into somewhat of a tourist trap. While one can still hike up, roads now pave the way for a leisurely ascent. There are jubilant young travelers taking selfies along the vista, and, presumably, vacationers seeking spiritual inspiration.

Although Metéora’s doors are open, old codes of respect and modesty are still enforced. Women who visit should wear dresses, according to tradition, or else they can expect to be turned away.

The great hope for Metéora is that its inhabitants will find the peace they are seeking, while its visitors may bring some of that peace home with them. And we can have the secluded mountain feel everywhere without even having to sell our cars.