A couple of interesting articles about St. Edward the Martyr — his short life and murder which happened near Corfe Castle on the 18th of March 978.

The following is an extract taken from the ‘Chambers Book of Days’ March 18th 1864, with regards to the death of Edward the king of England who was brutally murdered near Corfe Castle, Dorset.

Stained Glass Window at

Stained Glass Window at

Shaftesbury Abbey of

St. Edward by Rupert Moore

“The great King Edgar had two wives, first Elfleda, and, after her death, Elfrida, an ambitious woman, who had become queen through the murder of her first husband, and who survived her second; and Edgar left a son by each, Edward by Elfleda, and Ethelred by Elfrida. At the time of their father’s death, Edward was thirteen, and Ethelred seven years of age; and they were placed by the ambition of Elfrida, and by political events, in a position of rivalry. Edgar’s reign had been one continued struggle to establish monarchism, and with it the supremacy of the Church of Rome, in Anglo-Saxon England; and the violence with which this design had been carried out, with the persecution to which the national clergy were subjected, now caused a reaction, so that at Edgar’s death the country was divided into two powerful parties, of which the party opposed to the monks was numerically the strongest. The queen joined this party, in the hope of raising her son to the throne, and of ruling England in his name; and the feeling against the Romish usurpation was so great, that, although Edgar had declared his wish that his eldest son should succeed him, and his claim was no doubt just, the crown was only secured to him by the energetic interference of Dunstan. Edward thus became King of England in the year 975.

Edward appears, as far as we can learn, to have been an amiable youth, and to have possessed some of the better qualities of his father; but his reign and life were destined to be cut short before he reached an age to display them. He had sought to conciliate the love of his step-mother by lavishing his favour upon her, and he made her a grant of Dorsetshire, but in vain; and she lived, apparently in a sort of sullen state, away from court, with her son Ethelred, at Corfe in that county, plotting, according to some authorities, with what may be called the national party, against Dunstan and the government.

The Anglo-Saxons were all passionately attached to the pleasures of the chase, and one day—it was the 18th of March 978 — King Edward was hunting in the forest of Dorset, and, knowing that he was in the neighbourhood of Corfe, and either suffering from thirst or led by the desire to see his half-brother Ethelred, for whom he cherished a boyish attachment, he left his followers and rode alone to pay a visit to his mother. Elfrida received him with the warmest demonstrations of affection, and, as he was unwilling to dismount from his horse, she offered him the cup with her own hand. While he was in the act of drinking, one of the queen’s The Murder of King Edward the Martyr attendants, by her command, stabbed him with a dagger. The prince hastily turned his horse, and rode toward the wood, but he soon became faint and fell from his horse, and his foot becoming entangled in the stirrup, he was dragged along till the horse was stopped, and the corpse was carried into the solitary cottage of a poor woman, where it was found next morning, and, according to what appears to be the most trustworthy account, thrown by Elfrida’s directions into an adjoining marsh.

The young king was, however, subsequently buried at Wareham, and removed in the following year to be interred with royal honours at Shaftesbury. The monastic party, whose interests were identified with Edward’s government, and who considered that he had been sacrificed to the hostility of their opponents, looked upon him as a martyr, and made him a saint. The writer of this part of the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, who was probably a contemporary, expresses his feelings in the simple and pathetic words, ‘No worse deed than this was done to the Anglo race, since they first came to Britain.’

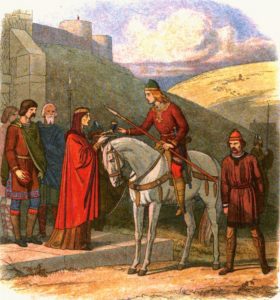

19th-century depiction by James William Edmund Doyle, Edward the Martyr is offered a cup of mead by Ælfthryth, widow of the late Edgar, unaware that her attendant is about to murder him!

19th-century depiction by James William Edmund Doyle, Edward the Martyr is offered a cup of mead by Ælfthryth, widow of the late Edgar, unaware that her attendant is about to murder him!

The story of the assassination of King Edward is sometimes quoted in illustration of a practice which existed among the Anglo-Saxons. Our forefathers were great drinkers, and it was customary with them, in drinking parties, to pass round a large cup, from which each in turn drunk to some of the company. He who thus drank, stood up, and as he lifted the cup with both hands, his body was exposed without any defence to a blow, and the occasion was often seized by an enemy to murder him. To prevent this, the following plan was adopted. When one of the company stood up to drink, he required the companion who sat next to him, or some one of the party, to be his pledge, that is, to be responsible for protecting him against anybody who should attempt to take advantage of his defenceless position: and this companion, if he consented, stood up also, and raised his drawn sword in his hand to defend him while drinking. This practice, in an altered form, continued long after the condition of society had ceased to require it, and was the origin of the modern practice of pledging in drinking. At great festivals, in some of our college halls and city companies, the custom is preserved almost in its primitive form in passing round the ceremonial cup—the loving cup, as it is sometimes called. As each person rises and takes the cup in his hand to drink, the man seated next to him rises also, and when the latter takes the cup in his turn, the individual next to him does the same.”

Extract from an article written by the George J. Bennett. titled ‘The Religious Foundations and Norman Castle of Wareham’ from the ‘Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society’ Volume 19 1898,

St. Edward the Martyr commemorative sign,

St. Edward the Martyr commemorative sign,

Corfe Castle village

The Saxon Chronicler asserts that in A.D. 979 the Saxon King Edward was slain at eventide at Corfe Gate, on the 18th March, and then he was buried at Wareham without any kind of kingly honours. Those acquainted with the records of Edward’s murder and burial are aware that the monkish historians affirm that three times the dead king’s body was discovered by supernatural lights:- 1. In a cottage at Corfe Gate. 2. By the light which appeared above the marshy ground. 3. By the light over the grave at Wareham.

When the treacherous blow had been dealt, the mortally wounded monarch rode hastily away, but, falling from loss of blood, he was dragged a considerable distance by his horse. We learn from Hutchins (Hutchins, 1st Ed., Vol I.p. 177.) that Elfrida immediately despatched some trusty servants to ascertain the result of her treachery. Russel (Russel’s Hist. Eng., p. 47.) informs us that they traced it by the blood, and found the king’s corpse much bruised and defaced. From conflicting records we gather that Edward’s body was found at the base of the hill, by what was afterwards termed St. Edward’s, or King Bridge. Elfrida then commanded that the body should be hidden in a cottage. The superstitious affirm that during the night, the house became illuminated by a blaze of miraculous light, by which the sight of a blind inmate was restored. On the site of that house a church was afterwards built. Corfe Castle Church is one of the very few in England dedicated to King Edward the Martyr.

The morning after the murder, when she had been informed of these circumstances, Elfrida commanded that Edward’s body should be removed from the cottage secretly, and hidden in a marshy place. This was done, and it is evident that only Elfrida’s confederates in guilt were entrusted with the work. When the guilty Queen had seen her orders executed, she, in order to avoid suspicion, left Corves-geiite, and retired to the Royal residence at Bere Regis. Ineffectual search continued to be made by Edward’s retainers for the body of their late master. At length their efforts were rewarded. The superstitious supposed that “a pillar of fire,” descending from heaven, illuminated the place where it was hid. Edward’s body was then carried to Waieham, and buried with as much secrecy by the late monarch’s friends as his enemies had used in hiding it. If Edward’s body was really concealed in one of the Purbeck peat bogs, Brannon says : “The astonishing power of peat would actually embalm the body ; the presence of animal matter evolve at a strong phosphorescent light, and the ‘ pillar of fire,’ in this case an ignis not factuus, would rest over it.” By accepting this theory the supposed miracle is accounted for. When writing of the discovery of Edward’s body in the marshy place, Hutching, quoting Brompton, observes : ” Some devout people of Wareham brought it to that town, to the church of St. Mary, and buried it in a plain manner (non regio more) on the east side, where a wooden church, (Hutchins, 2nd Ed., Vol. I, p. 177. ) afterwards built by religious persons, was to be seen in that author’s time.” From Brompton, the historian, we learn some important facts. First, that the actual spot where Edward was buried at Wareham was unknown, even to the ecclesiastics, so secret was the burial. In his Magna Britannia, (Dorsetshire, p. 562. ) published 1720, the Rev. T. Cox shows that it was only by a supposed miracle that Edward’s burial place at Wareham was discovered. He writes of Edward thus : — ” His body had been clandestinely buried at Wareham, in hopes that his murder might have been concealed ; but it being afterwards discovered by a miraculous blaze of light hanging over his tomb.” The reports of the miracles and wonders at Wareham, were, according to Malmesbury, wide spread ; and much good is said to have been effected by the sanctity of the royal remains. As an historical fact, Brompton, Abbot of Forvant, informs us that the body of King Edward was buried, not in, but on the east side of St. Mary’s Church. The fact that Edward was not buried in a church, and the statement of some, probably correct, that the body was discovered in unconsecrated ground, would be ample reason for the removal of the body from Wareham. When the report of the miracles (Dorsetshire, p. 562.) and discovery of the body had been communicated to Elfrida, she granted permission for Edward’s remains to be removed to Shaftesbury Abbey, and there royally entombed. We are informed by the Saxon Chronicler that in A.D. 980 ” St. Dunstan and Alfere, the ealderman, fetched the holy king’s body, St. Edward’s, from Wareham, and bore it with much solemnity to Shaftesbury.” For his information, though brief, we are under an obligation to Brompton. He tells us that the Saxon King Edward was buried on the east side of St. Mary’s, and that on the spot where Edward had been buried a wooden church was built. And what is also important, Brompton asserts that the wooden church was still existing when he wrote at the close of the 14th century. Here we have a substantial proof that the body of King Edward was never buried in St. Mary’s Church ; that church was also existing. None of the monkish historians tell us that King Edward was buried in St. Mary’s Church, nor do the modern make any such statement.

That the late Mr. T. Bond accepted Brompton’s statement is certain. In his ” Corfe Castle ” he writes : — ” Search being made for the body, the place where it was concealed was discovered, and thereupon some devout people of Wareham, having conveyed the corpse to the church of St. Mary, in that town, buried it in a plain and homely manner on a spot where religious men afterwards built a wooden church, still standing when Brompton’s Chronicle was written.”

When, in 1841, the nave of Lady St. Mary’s was demolished, and the original St. Mary’s shortened, some ancient stone coffins were discovered and destroyed. One, however, was preserved, the remarkable boat-shaped sarcophagus of Purbeck marble now standing at the entrance to the church. In circumference it measures 17ft. it is 8ft. 2in. in length ; width at shoulders, 30in. ; greatest outer depth, 17in. ; it is estimated to weigh considerably over a ton. Some think King Edward was buried in that coffin; competent judges assert that it is much too modern. Supposing that the King’s body had been laid therein, it would have been an utter impossibility to have buried a coffin of such size and weight secretly in so small a building, 12ft. wide and about 45ft. long. To such a secret burial as King Edward had, this huge coffin would have been a mostserious hindrance. The original St. Mary’s is now used as a choir vestry and called King Edward’s Chapel.

Glossary

Dorsetshire = Dorset

Corves-geiite = Corfe Castle

Waieham = Wareham

Links: Originally published on the Dorset County Museum website (no longer available).

Leave a Comment