Born in Marton, near Middlesborough, James Cook would go on to become one of the most famous explorers in British maritime history.

Indeed, young James’ childhood was nothing remarkable, and following his rudimentary education, Cook became an apprentice to William Sanderson, a local grocer. After 18 months working next to Staithes’ busy harbour, James felt the calling of the sea. Sanderson – not wanting to stand in the young man’s way – introduced Cook to his friend, John Walker, a ship owner from Whitby, who took him on as an apprentice seaman.

Cook lived in the Walker family house in Whitby and went to school with the other apprentices in the town. Cook worked hard, and was soon serving on one of Walkers’ “cats”, the Freelove. Cats were hardy ships, built in Whitby to take coal down the coast to London. Cook was a quick learner and rapidly established himself as one of the most promising apprentices in Walkers’ care.

In 1750, Cook’s apprenticeship with the Walkers ended, though he carried on working for them as a seaman. As always with Cook, it wasn’t long before he was promoted, and in 1755, he was offered the command of the Friendship, a cat he was familiar with. For many, this would have been the realisation of an ambition and they would have grasped the chance with both hands. Cook, however, wanted more than to spend his remaining years sailing in coastal waters in poor weather, so he politely turned down the Walkers’ offer and joined the Royal Navy.

Above: Captain Cook in 1776

Cook was placed on board H.M.S. Eagle, and in November 1755 he saw his first (albeit rather mundane) action. The French ship, Esperance, was in poor shape before it met the Eagle and her squadron, and it did not take long before she was battered into submission. Sadly for Cook, the Esperance was set alight during the short battle and could not be saved, thus denying the British the prize.

Two years later, Cook was posted to the larger H.M.S. Pembroke, and in early 1758 he set sail for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Service in North America proved to be the making of Cook. After the capture of Louisburg in late 1758, the Pembroke was part of the expedition tasked with surveying and mapping the St. Lawrence River to create an accurate chart, thus allowing British ships to navigate safely through the area.

In 1762 Cook was back in England, where he married Elizabeth Batts. The marriage produced six children – though, unfortunately, Mrs. Cook was to outlive them all.

While Cook was marrying, Admiral Lord Colville was writing to the Admiralty, mentioning his “experience of Mr Cook’s genius and capacity” and suggesting that he be considered for more cartography. The Admiralty took notice and in 1763 Cook was instructed to survey the 6,000-mile coast of Newfoundland.

After two successful seasons in Newfoundland, Cook was asked to observe the 1769 transit of Venus from the South Pacific. This was necessary to determine distances between the Earth and the Sun, and the Royal Society needed observations to be carried out from points across the globe. The added benefit of sending Cook into the South Pacific was that he could search for the fabled Terra Australis Incognita, the Great Southern Continent.

Cook was, fittingly, given a ship to take to Tahiti and beyond. A three-year-old merchant collier, the Earl of Pembroke, was purchased, re-fitted and renamed. The Endeavour was to become one of the most famous ships ever to put to sea.

In 1768 Cook set off for Tahiti, stopping briefly at Madeira, Rio de Janeiro and Tierra del Fuego. His observation of the transit of Venus went without a hitch, and Cook was able to explore at his leisure. He charted New Zealand with astonishing accuracy, making just two mistakes, before moving on to what we now know to be the eastern coast of Australia.

Above: Captain Cook landing at Botany Bay.

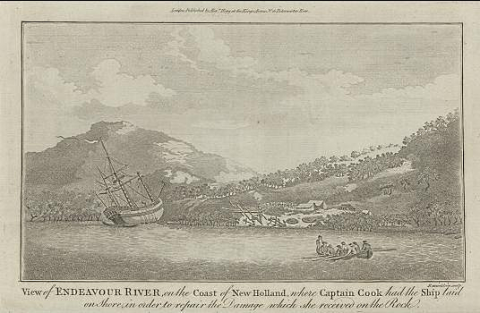

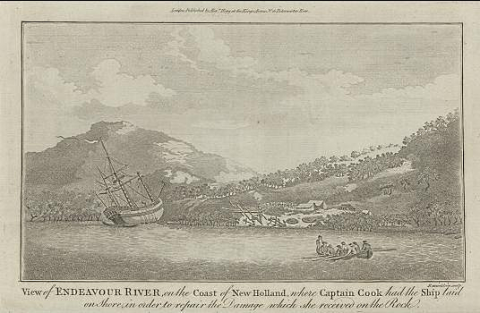

Cook landed in Botany Bay, just south of modern-day Sydney and claimed the land for Britain. For four more months, Cook charted the coast and named it New South Wales. It was easy going until 10th June, when the Endeavour hit the Great Barrier Reef. The hull was holed and Cook was forced to make for land in order to repair the vessel. The Endeavour made it to the mouth of a river, where she was beached for so long the settlement there became known as Cooktown.

Above: The HMS Endeavour after being damaged by the Great Barrier Reef. The enscription reads “View of Endeavour River on the coast of New Holland, where Captain Cook had the ship land on shore in order to repair the damage which she received on the rock”.

On the 13th July 1771 the Endeavour finally returned, and Cook’s first voyage was over. However, it was exactly 12 months later that Cook set sail once more, this time tasked with sailing further south and searching for the elusive Great Southern Continent.

This time, Cook was given two “cats”. The ships were fitted out for the voyage and named Resolution and Adventure.

Though Cook was a sceptic where the Southern Continent was concerned, he dutifully made three sweeps of the Antarctic Circle, in the course of which he sailed further south than any explorer had sailed before and became the first man to cross both the Arctic and Antarctic Circles. Cook returned to England in 1775 with little else to show for his three years at sea.

By mid-1776, Cook was on another voyage, again on board Resolution, with Discovery in tow. The aim was to find a navigable passage across the top of North America between the Pacific and the Atlantic – a task in which he was eventually unsuccessful.

The voyage became an even greater failure in 1779, when Cook called in at Hawaii on the way back to England. Resolution had stopped there on the way, and the crew had been treated relatively well by the locals. Once again, the Polynesians were pleased to see Cook and trade was carried out fairly amicably. He departed on February 4th, but bad weather forced him to turn back with a broken foremast.

This time relations were not so friendly, and the theft of a boat led to an altercation. In the ensuing row, Cook was mortally wounded. Today an obelisk still marks the spot where Cook fell, reachable only by small boats. Cook was given a ceremonial funeral by the locals, though what happened to his body is unclear. Some say it was eaten by the Hawaiians (who believed in recovering the strength of their enemies by eating them), others say that he was cremated.

Above: Cook’s death in Hawaii, 1779.

Whatever happened to his body, Cook’s legacy is far-reaching. Towns across the world have taken his name and NASA named their shuttles after his ships. He expanded the British Empire, forged links between nations, and now his name alone fuels economies.Born in Marton, near Middlesborough, James Cook would go on to become one of the most famous explorers in British maritime history.

Indeed, young James’ childhood was nothing remarkable, and following his rudimentary education, Cook became an apprentice to William Sanderson, a local grocer. After 18 months working next to Staithes’ busy harbour, James felt the calling of the sea. Sanderson – not wanting to stand in the young man’s way – introduced Cook to his friend, John Walker, a ship owner from Whitby, who took him on as an apprentice seaman.

Cook lived in the Walker family house in Whitby and went to school with the other apprentices in the town. Cook worked hard, and was soon serving on one of Walkers’ “cats”, the Freelove. Cats were hardy ships, built in Whitby to take coal down the coast to London. Cook was a quick learner and rapidly established himself as one of the most promising apprentices in Walkers’ care.

In 1750, Cook’s apprenticeship with the Walkers ended, though he carried on working for them as a seaman. As always with Cook, it wasn’t long before he was promoted, and in 1755, he was offered the command of the Friendship, a cat he was familiar with. For many, this would have been the realisation of an ambition and they would have grasped the chance with both hands. Cook, however, wanted more than to spend his remaining years sailing in coastal waters in poor weather, so he politely turned down the Walkers’ offer and joined the Royal Navy.

Above: Captain Cook in 1776

Cook was placed on board H.M.S. Eagle, and in November 1755 he saw his first (albeit rather mundane) action. The French ship, Esperance, was in poor shape before it met the Eagle and her squadron, and it did not take long before she was battered into submission. Sadly for Cook, the Esperance was set alight during the short battle and could not be saved, thus denying the British the prize.

Two years later, Cook was posted to the larger H.M.S. Pembroke, and in early 1758 he set sail for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Service in North America proved to be the making of Cook. After the capture of Louisburg in late 1758, the Pembroke was part of the expedition tasked with surveying and mapping the St. Lawrence River to create an accurate chart, thus allowing British ships to navigate safely through the area.

In 1762 Cook was back in England, where he married Elizabeth Batts. The marriage produced six children – though, unfortunately, Mrs. Cook was to outlive them all.

While Cook was marrying, Admiral Lord Colville was writing to the Admiralty, mentioning his “experience of Mr Cook’s genius and capacity” and suggesting that he be considered for more cartography. The Admiralty took notice and in 1763 Cook was instructed to survey the 6,000-mile coast of Newfoundland.

After two successful seasons in Newfoundland, Cook was asked to observe the 1769 transit of Venus from the South Pacific. This was necessary to determine distances between the Earth and the Sun, and the Royal Society needed observations to be carried out from points across the globe. The added benefit of sending Cook into the South Pacific was that he could search for the fabled Terra Australis Incognita, the Great Southern Continent.

Cook was, fittingly, given a ship to take to Tahiti and beyond. A three-year-old merchant collier, the Earl of Pembroke, was purchased, re-fitted and renamed. The Endeavour was to become one of the most famous ships ever to put to sea.

In 1768 Cook set off for Tahiti, stopping briefly at Madeira, Rio de Janeiro and Tierra del Fuego. His observation of the transit of Venus went without a hitch, and Cook was able to explore at his leisure. He charted New Zealand with astonishing accuracy, making just two mistakes, before moving on to what we now know to be the eastern coast of Australia.

Above: Captain Cook landing at Botany Bay.

Cook landed in Botany Bay, just south of modern-day Sydney and claimed the land for Britain. For four more months, Cook charted the coast and named it New South Wales. It was easy going until 10th June, when the Endeavour hit the Great Barrier Reef. The hull was holed and Cook was forced to make for land in order to repair the vessel. The Endeavour made it to the mouth of a river, where she was beached for so long the settlement there became known as Cooktown.

Above: The HMS Endeavour after being damaged by the Great Barrier Reef. The enscription reads “View of Endeavour River on the coast of New Holland, where Captain Cook had the ship land on shore in order to repair the damage which she received on the rock”.

On the 13th July 1771 the Endeavour finally returned, and Cook’s first voyage was over. However, it was exactly 12 months later that Cook set sail once more, this time tasked with sailing further south and searching for the elusive Great Southern Continent.

This time, Cook was given two “cats”. The ships were fitted out for the voyage and named Resolution and Adventure.

Though Cook was a sceptic where the Southern Continent was concerned, he dutifully made three sweeps of the Antarctic Circle, in the course of which he sailed further south than any explorer had sailed before and became the first man to cross both the Arctic and Antarctic Circles. Cook returned to England in 1775 with little else to show for his three years at sea.

By mid-1776, Cook was on another voyage, again on board Resolution, with Discovery in tow. The aim was to find a navigable passage across the top of North America between the Pacific and the Atlantic – a task in which he was eventually unsuccessful.

The voyage became an even greater failure in 1779, when Cook called in at Hawaii on the way back to England. Resolution had stopped there on the way, and the crew had been treated relatively well by the locals. Once again, the Polynesians were pleased to see Cook and trade was carried out fairly amicably. He departed on February 4th, but bad weather forced him to turn back with a broken foremast.

This time relations were not so friendly, and the theft of a boat led to an altercation. In the ensuing row, Cook was mortally wounded. Today an obelisk still marks the spot where Cook fell, reachable only by small boats. Cook was given a ceremonial funeral by the locals, though what happened to his body is unclear. Some say it was eaten by the Hawaiians (who believed in recovering the strength of their enemies by eating them), others say that he was cremated.

Above: Cook’s death in Hawaii, 1779.

Whatever happened to his body, Cook’s legacy is far-reaching. Towns across the world have taken his name and NASA named their shuttles after his ships. He expanded the British Empire, forged links between nations, and now his name alone fuels economies.