Chinese ink painting—a captivating and enduring art form—originated in the Tang Dynasty (618–907). Defined by its inherent simplicity, ink painting uses basic tools such as paper, brushes, and black ink. Yet it also possesses a profound complexity through its ability to portray rich spectrums of visual narratives through the nuanced manipulation of tonality and shading.

It takes years for artists working with Chinese ink painting to hone their skills and master the varied brush techniques. That’s because adjusting the amount of ink and pressure within a single brushstroke can create substantial variations in tonality.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at eight of the greatest works of Chinese ink painting. We hope to draw your attention to the tranquil beauty and exceptional details these unique paintings express, explore their cultural significance, and contemplate the hidden meanings behind their captivating ink strokes.

Chinese Ink Painting 1:

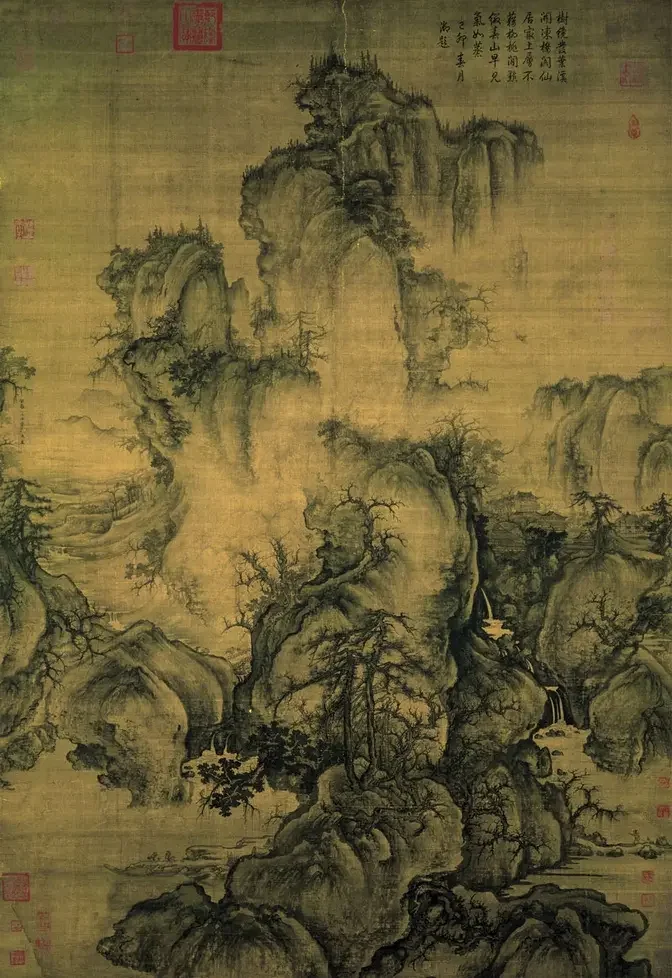

北宋郭熙《早春圖》

Title: Early Spring, c.1072, Northern Song Dynasty

Painter: Guo Xi (c.1020–c. 1090)

Provenance: National Palace Museum, Taiwan

Medium: Ink on silk

Size: 28.6h x 36.5w cm

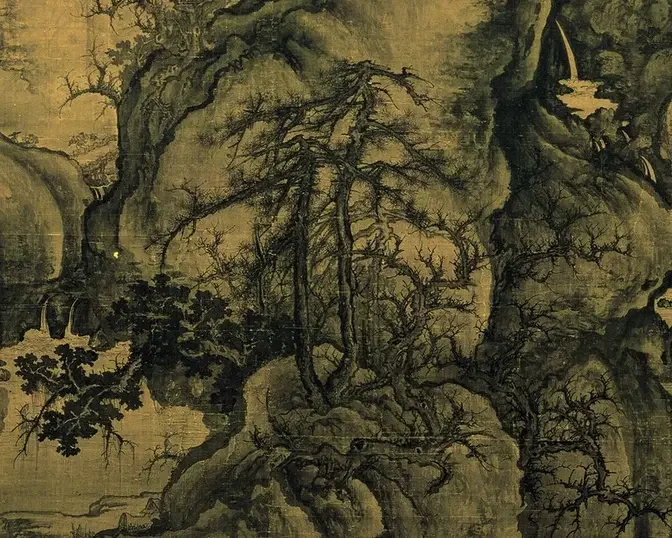

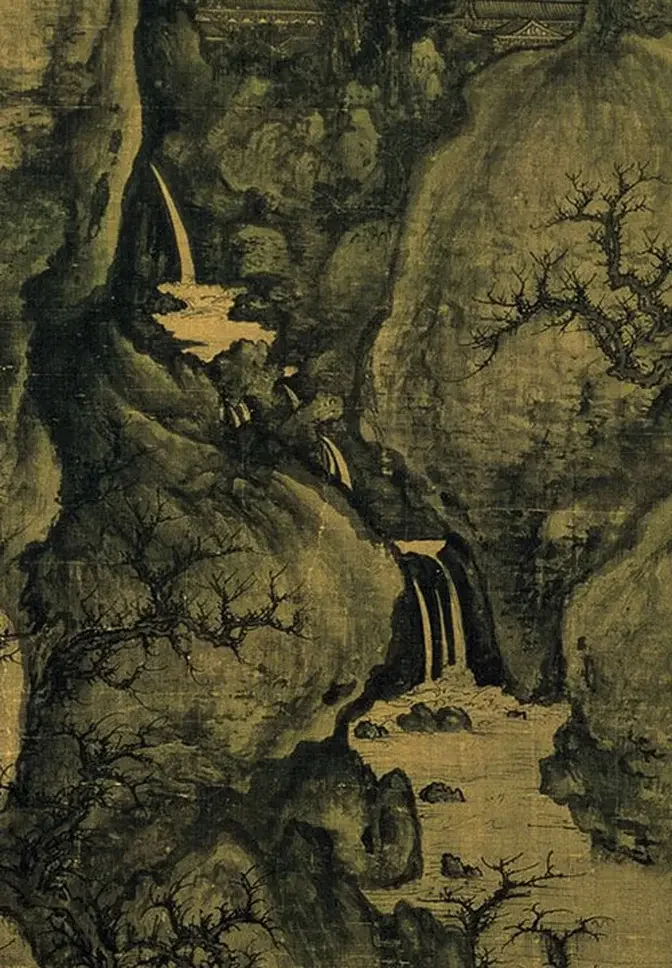

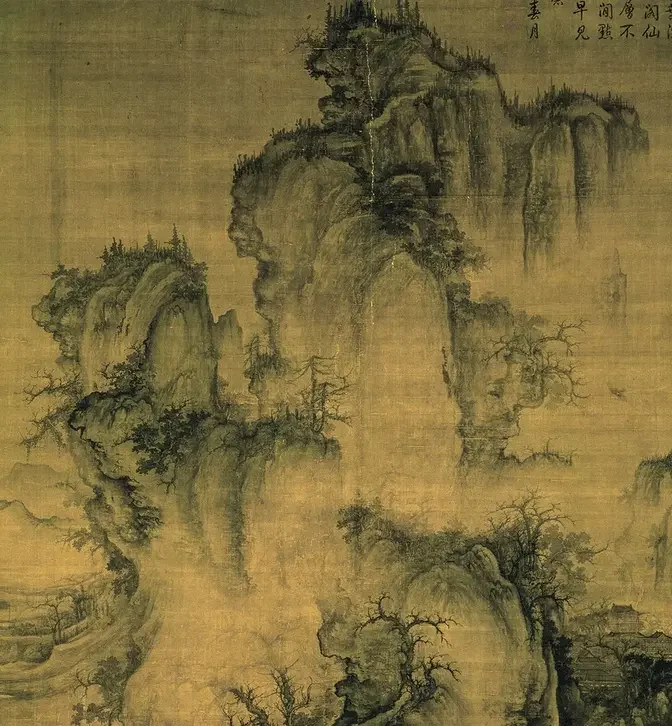

The piece Early Spring (1072) by Guo Xi, is considered one of the greatest ink paintings of China’s Northern Song Dynasty, an era when landscape paintings reached a greater level of sophistication. Guo’s painting depicts the mountains in early spring, yet he doesn’t use colors to emphasize the blush of the peach blossoms or the vividness of the newly sprouted grass. Still, with nothing but ink, Guo has succeeded in capturing the earth’s renewal after a harsh winter.

As the earth awakens from its winter slumber, the mountains are shrouded in heavy mist, depicted through washes of ink and amorphous brush strokes. With the melting of the ice and snow, the mountain springs become reanimated and trickle over the rocks once more. Upon the large rock at the foot of the hill is a piece of dead wood from which new shoots sprout, further signifying the renewal and resilience of life.

Guo wrote texts about the philosophies and techniques of landscape ink painting, which became highly influential and valuable guides for later painters. Viewers standing before Guo’s landscape pieces may find themselves surprised by the paintings’ immersive quality. One can almost hear the merry chirping of birds and the joyful gurgling of flowing water.

Guo explained his love for landscapes in his famous treatise Mountains and Waters: ”The din of the dusty world and the locked-in-ness of human habitations are what human nature habitually abhors; on the contrary, haze, mist, and the haunting spirits of the mountains are what human nature seeks, and yet can rarely find.”

In Guo’s landscape painting, water is the lifeblood of the mountains. In Early Spring, a waterfall surges down from the highest peak and flows down into a valley, forming a line of continuity in the painting and transforming the distinct mountains into a single breathing, sentient being.

One of Guo’s iconic techniques is the layering of ink washes to create realistic three-dimensional shapes. In this painting, the higher peaks are meticulously framed by expanses of white space, appearing to be enveloped by ethereal clouds.

Chinese Ink Painting 2:

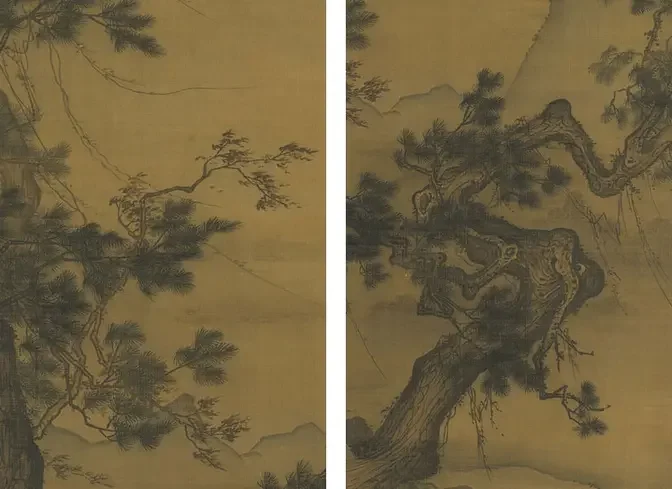

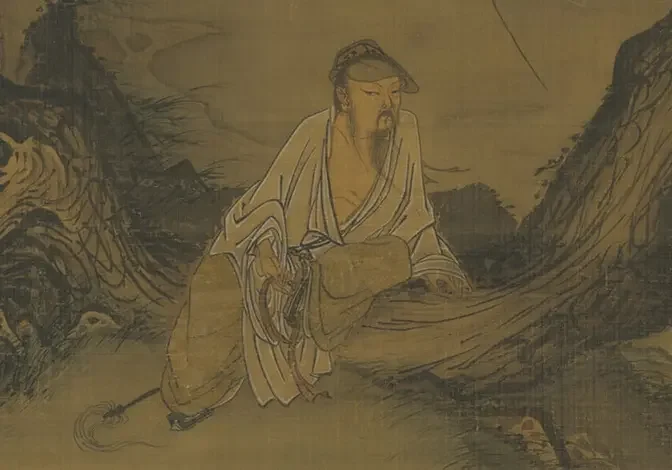

南宋馬麟《靜聽松風圖》

Title: Quietly Listening to Wind in the Pines, c.1246, Southern Song Dynasty

Painter: Ma Lin (c.1180–c. 1256)

Provenance: National Palace Museum, Taiwan

Medium: ink and color on silk

Size: 226.6 h x110.3w cm

As you observe this painting, can you hear the soft music of the rustling pine needles and feel the gentle caress of the mountain breeze?

The piece Quietly Listening to the Wind in the Pines is a masterpiece by Southern Song Dynasty painter Ma Lin, and serves as a display of his exceptional compositional talent. Like all traditional Chinese paintings, the human figures are not necessarily meant to be the painting’s focal point. Rather, to portray the Taoist philosophy of being one with nature, the human figure is nestled within the grandeur of the natural landscape, becoming an organic part of it.

Ma depicts a sage-like scholar sitting beneath a tree, listening to nature’s melodies. He appears to be in deep contemplation, exuding an otherworldly aura as though he is utterly unbothered by worldly affairs. The pine needles, the bark, and the man’s wispy beard are all painted with remarkable detail. Extremely fine brush strokes are employed to bring out the different textures of the subjects.

The faint mountains in the painting’s background remind the viewer that the vastness of nature extends far beyond the confines of this painting, thus giving the piece a three-dimensional depth. Meanwhile, the careful depiction of swaying branches gives the wind a visible manifestation, bestowing the painting with a sense of animation.

Chinese Ink Painting 3:

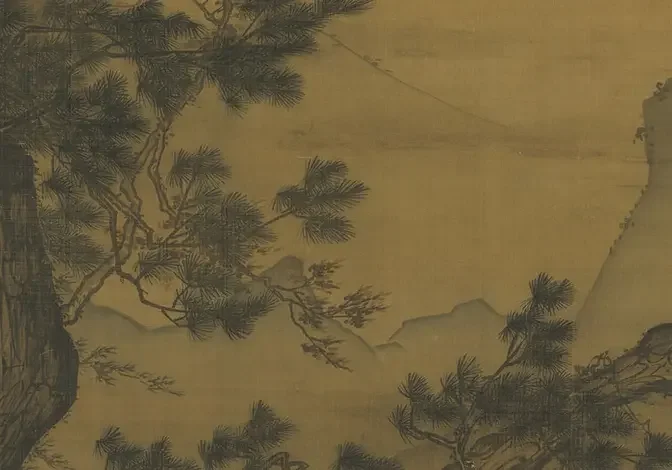

宋李唐《萬壑松風圖》

Title: Wind in Pines Among a Myriad Valleys, Song Dynasty

Painter: Li Tang (circa 1049 – after 1130)

Provenance: National Palace Museum, Taiwan

Medium: ink and color on silk

Size: 188.7 h x139.8w cm

The piece Wind in Pines Among Myriad Valleys is a landscape painting by Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279) painter Li Tang, who took part in Emperor Huizong’s imperial painting academy. Li and his disciples made adjustments to Northern Song Dynasty painting styles, which eventually developed into a style unique to that period, emphasizing ink variation and the implementation of corner views.

In this painting, Li used a brushwork technique known as “axe-cut” to render the rugged texture of the mountainsides. The piece, made three years before the Northern Song Dynasty ended, is one of the last examples of the dynasty monumental landscape style.

Clouds are strategically placed to split the mountainside, alleviate the scenery’s density, and ensure the painting doesn’t seem oppressive to the viewer. The clouds and mist in this painting are depicted by leaving the paper blank, a technique commonly used in traditional Chinese paintings.

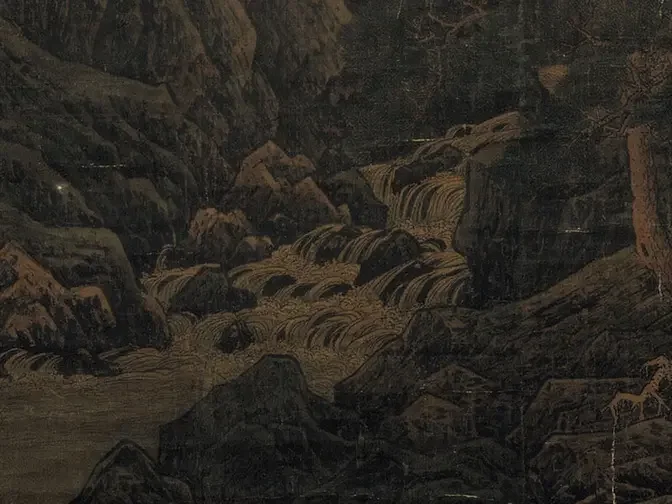

Contrasting the steady stillness of the unmoving mountains are the trickling waterfalls and flowing streams. At the foot of the mountain, the rapids tumble over the rocks, while the detailed portrayal of the spraying water suggests rushing movement. Yet once the stream flows into a larger body of water, it appears to immediately become tranquil, as though it has finally found a place to rest.

The superb level of realism Li achieved in this painting can be observed in the details of the rocks. The roughness of those forming the face of the mountain is brought out with small, meticulous brushstrokes.

Furthermore, the environment of the rocks is also taken into careful consideration, as the latter vary in appearance depending on what area of the mountain they are in. For example, the rocks near the water are painted with thick ink to appear wet, while the rocks higher up are painted with a lighter color to showcase their dryness.

Chinese Ink Painting 4:

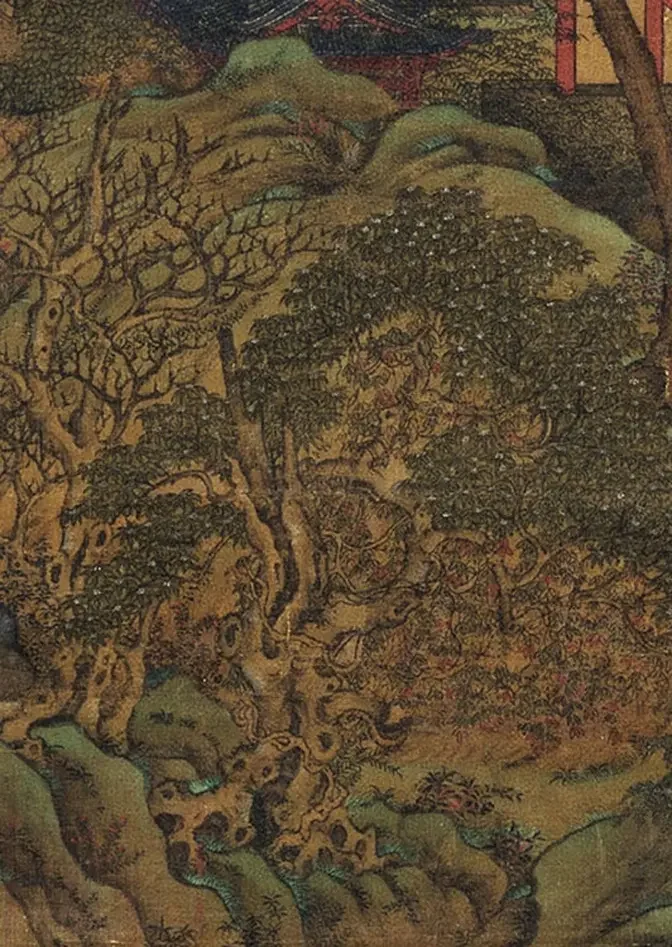

北宋初范寬《谿山行旅圖》

Title: Travelers among Mountains and Streams, Northern Song Dynasty

Painter: Fan Kuan (960 – 1030)

Provenance: National Palace Museum, Taiwan

Medium: ink and slight color on silk

Size: 206.3 h x 103.3 w cm

The painting Travelers Among Mountains and Streams is the only surviving work of Northern Song Dynasty painter Fan Kuan (960-1030). A classic example of the Northern Song monumental landscape style, this painting is nearly seven feet big, serving as a powerful rendering of a mountain landscape.

Landscape paintings have always been a significant genre in the Chinese art tradition. The Taoist teaching of being one with nature has elevated natural landscapes to a philosophical level. Although little is known about Fan, we do know that he lived as a recluse in the mountains after having experienced the political turmoil of the Five Dynasties period and that he had a passion for wine and mountains.

The ancient Chinese liked to imagine mountains as the homes of immortal beings, and a viewer of Fan’s painting can easily believe that the mountains he has expertly rendered are such places.

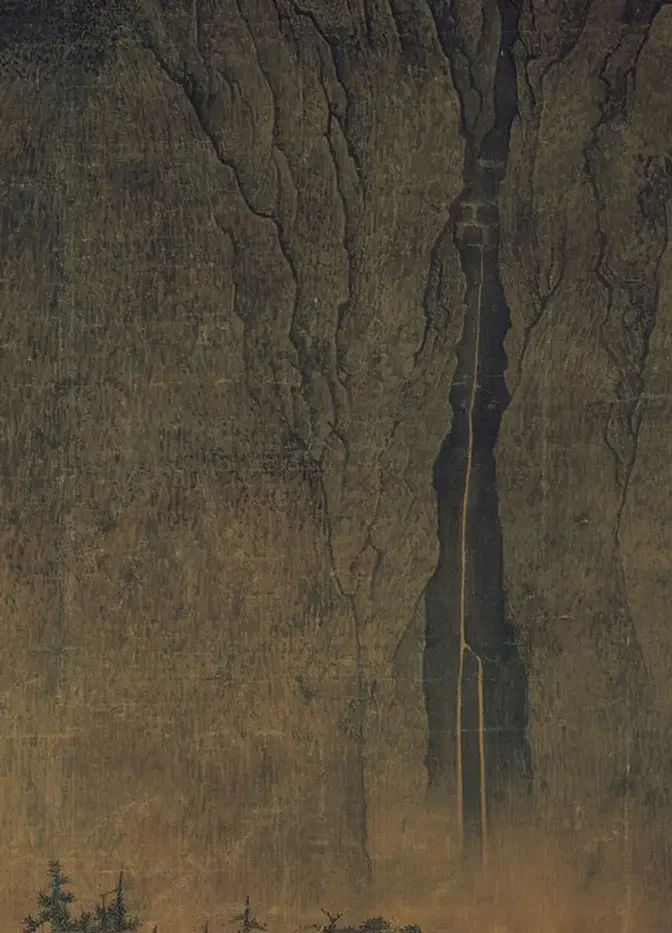

The towering mountains immediately catch the viewer’s attention as a breathtaking display of nature’s grandiosity. Fan uses lines of varying degrees of boldness, as well as texturing and shading techniques to accurately capture the texture of the mountain rocks and enhance the mountain’s three-dimensional appearance.

A waterfall cascades down the mountainside, disappearing behind a misty veil and bringing the viewer’s attention to the foreground.

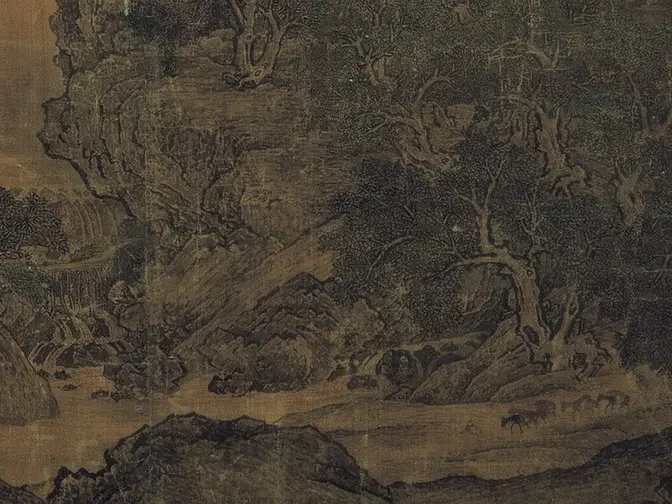

In the painting’s foreground, we can see a wide road flanked by large boulders and a stream surrounded by gnarled pines. Despite the mention of travelers in the painting’s title, the two human figures and the mule train on the road are tiny and insignificant compared to the colossal mountains that serve as the background.

The only other sign of human life within these mountains is the temple nestled in the forest on the cliffs, yet it’s a subtle presence. It’s through this portrayal of human activity that Fan reminds viewers of the smallness of humans before the majestic magnitude of nature. The foreground’s details are so fine that visitors often use binoculars to get a closer look at its exquisite artistry.

Chinese Ink Painting 5:

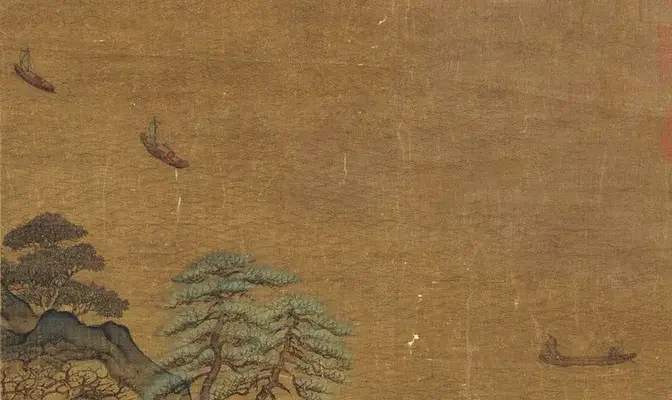

唐 李思训《江帆楼阁图》

Title: Sailboats and Pavilions, Tang Dynasty

Painter: Li Sixun (651–716)

Provenance: National Palace Museum, Taiwan

Medium: ink and color on silk

Size: 101.9 h x54.7 w cm

Since ancient times, the Chinese have been particularly fond of spring outings. As the season of revival, spring was a particular source of inspiration for the literati and artists.

The piece Sailing Boats and a Riverside Mansion, painted by Tang Dynasty artist Li Sixun, depicts a vivid spring scene in which people are reconnecting with nature. It’s an example of a Chinese gold-and-green landscape painting, a subgenre of Chinese landscape painting that uses golden, azurite blue, and mineral green paint as its central colors.

Amid the gold, blue, and green, we see the red and black rooftop of a building in which a person stands.

Walking along the riverbank near the bottom of the painting are four men; one sits atop a mule, another leads it, while their two companions follow behind. Meanwhile, two more men stand further up the painting by the river bend. They seem to be chatting as they observe the scene before them. The figures in the painting are all wearing Tang Dynasty attire, and the artist uses simple lines to depict the soft folds in their clothing.

Upon closer inspection, one sees different trees featured in the painting. Aside from evergreen trees such as pines and firs, there are also various species of deciduous trees sporting lush new leaves, a wispy willow, and trees with blooming red blossoms. Every detail is finely lined with black ink.

Li uses faint wavy lines to depict the rippling river water. Floating in the distance are three small sailboats. From afar, they look like a mere outline, yet close up, we see that the artist painted the boats in great detail. The sail, mast, and cabin are all meticulously painted and colored, and a small human figure manning the boat is visible as well.

The mountain slope separates the painting into two halves; the flourishing vegetation of one half contrasts the open flowing water of the other. Upon seeing this painting, we’re struck by how alive it feels. We can almost hear the water lapping the riverbank, hear the sound of human voices, and smell the fresh spring air infused with the fragrance of flowers and pines.

The piece Sailing Boats and a Riverside Mansion awakens in the viewer a desire to join the figures in the painting and see the full breadth of the scenery they’re admiring.

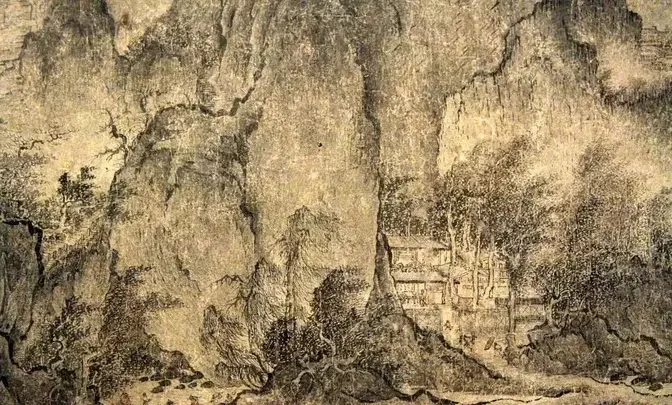

Chinese Ink Painting 6:

北宋 燕文貴 (江山樓觀圖)

Title: Pavilions Among Mountains and Rivers, Northern Song Dynasty

Painter: Yan Wengui (ca. 967-1044)

Provenance: Osaka City Museum of Fine Art

Medium: ink on Xuan paper

Size: 31.9 h x 161.2 w cm

A renowned painter during the early Northern Song Dynasty, Yan Wengui is primarily known for his landscape paintings. Formerly a soldier, Yan entered the Hanlin Academy—an academic institution of elite scholars under the imperial court—where he worked on producing wall paintings.

A renowned painter during the early Northern Song Dynasty, Yan Wengui is primarily known for his landscape paintings. Formerly a soldier, Yan entered the Hanlin Academy—an academic institution of elite scholars under the imperial court—where he worked on producing wall paintings.

Yan’s paintings were so exquisite and elegant that they were referred to as “Yan-style scenes,” and came to represent one of the two major schools of northern landscape painting.

Yan’s work Pavilions Among Mountains and Rivers depicts a panoramic scene along a river. The artist uses the “axe-cut” texturing technique in his brush strokes to bring out the roughness of the mountains and rocks. Short, dense strokes made with coarse brush are used to outline the contours of the rocky mountainsides.

As the scroll is unrolled, rising hills blanketed by lush vegetation are revealed, a prelude to the towering peaks yet to be seen.

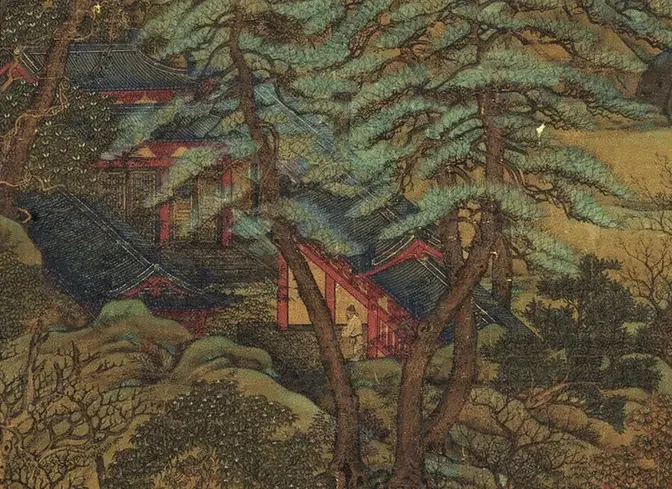

As one moves further toward the middle of the scroll, the misty clouds shrouding the mountains begin to thicken, infusing the landscape with a refined, celestial aura. Pavilions and buildings stand quietly amidst the natural scenery. They’re smaller and less majestic than the sweeping mountains, but just as valuable to the painting’s overall appearance.

The branches and trunks of the pines in the painting lean towards the right, conveying the presence of a powerful mountain wind. Further emphasis on the wind can be discovered in the more minute details. For example, we see three people returning to a village in the foothills, and one of the three figures is holding an umbrella in front of him, as though he is pushing against the wind.

The branches and trunks of the pines in the painting lean towards the right, conveying the presence of a powerful mountain wind. Further emphasis on the wind can be discovered in the more minute details. For example, we see three people returning to a village in the foothills, and one of the three figures is holding an umbrella in front of him, as though he is pushing against the wind.

At the end of the scroll is the climax of the entire mountain range. Cradled in the valleys of the layered mountains are more buildings, while careful scrutiny of the painting’s details reveals a company of woodcutters—some on steeds and others on foot—returning with chopped wood.

A waterfall cascades from the mountain peak, rushing to meet the surging river below, which flows beyond the painting and invites viewers to break past the limits of the scroll and extend the grand scenery of their imaginations.

Chinese Ink Painting 7:

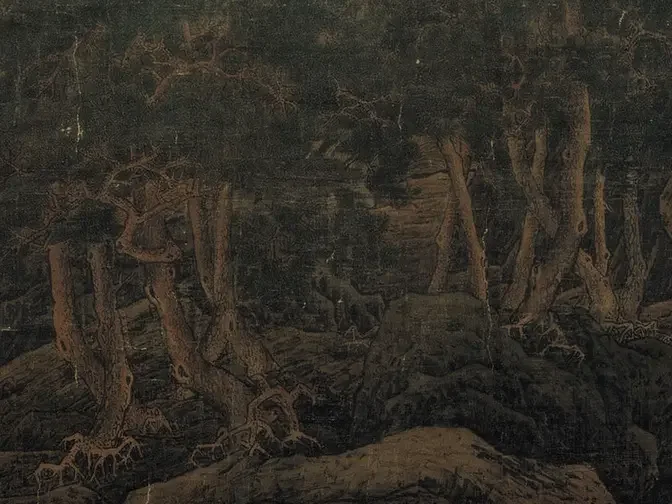

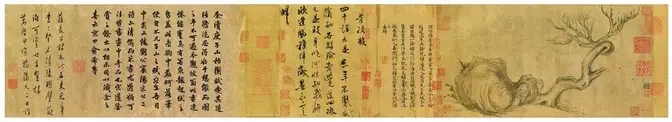

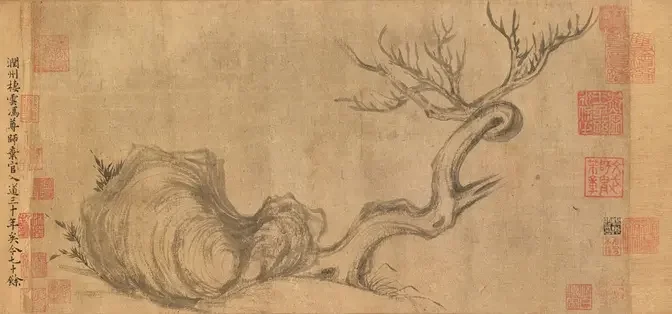

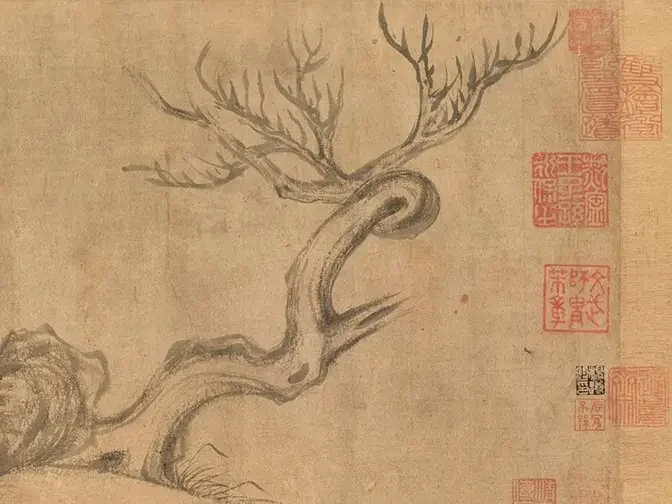

苏东坡《枯木怪石图》

Title: Withered Tree and Strange Rock, Northern Song Dynasty

Painter: Su Shi (1037 – 1101)

Provenance: Private Collection

Medium: ink on Xuan paper

Size: 26.3h x 50w cm

Hailed as one of “The Eight Great Men of Letters of the Tang and Song Dynasties” and a major literary and political figure of the Song Dynasty, Su Shi was not only an acclaimed poet and essayist, but also a painter.

On November 26, 2018, this painting, Wood and Rock, was sold at Christie’s Autumn Auction for a final price of 463.6 million Hong Kong dollars, which is just over 56 million USD. This set a new record for the highest auction price of ancient Chinese paintings.

The painting is very simple, depicting a withered tree and a peculiarly shaped rock. The tree, though bent by its years, exudes a defiant spirit. There’s a twist in the tree’s trunk, and its top branches, resembling antlers, reach towards the sky.

The tree in the painting is withered and dead, but we can see that although its figure is bent, its spirit is unbent. The same can be said about the spirit that shines through Su’s poetry, from which readers can observe his determined resolve to remain optimistic regardless of the hardships thrown along his way.

With its unique shape, can also be interpreted as another reflection of Su’s spontaneous and individualistic personality. Peeking out from behind the rock are sprouts of grass and bamboo. These are signs of life and hope, contrasting the lifeless rock and tree, reminding the viewer that although one’s setting may seem bleak, there’s always something to celebrate, as long as we look for it in the more minute elements of life.

Chinese Ink Painting 8:

《雙喜圖》軸, 崔白

Title: Magpies and Hare, 1016, Northern Song Dynasty

Painter: Cui Bai (fl. 1050–1080)

Provenance: National Palace Museum, Taiwan

Medium: ink and color on silk

Size: 193.7h x 103.4w cm

It wasn’t until the 1960s when the signature of Northern Song Dynasty painter Cui Bai was discovered on a branch, that Cui was identified as the creator of this painting. Known as Magpies and Hare and also referred to as the Song Double Happiness Scroll, we nonetheless don’t know the original title the artist intended for the piece.

The bare branches and barren grass we see in the painting are a sign of late autumn. A pair of magpies landing on a branch have momentarily caught a hare’s attention. The hare curiously observes the birds over its shoulder with one paw suspended in mid-air.

The animals are all accurately painted with meticulous detail. The hare’s brown and black fur is mottled, a sign that it has already grown a winter coat and another hint that the scene in the painting is set in late autumn.

The animals are all accurately painted with meticulous detail. The hare’s brown and black fur is mottled, a sign that it has already grown a winter coat and another hint that the scene in the painting is set in late autumn.

The fur’s texture is created with smudges and fine strokes, and one can see that Cui paid close attention to adjusting the fur length and texture according to what part of the hare’s body it covers. For example, the fur along the hare’s spine is longer and fluffier, while the fur on its legs is shorter and coarser.

The magpies in the painting are just as aware of the hare’s presence as the hare is of theirs. They can be seen cawing at the hare. The magpies’ tail and wing feathers are intricately outlined with thin ink.

The painting Magpies and Hare is ingeniously composed to resemble the structure of a Taoist taiji (yin and yang) symbol. The curved branches and slope subtly divide the image in half, and we find the hare and one of the magpies in opposite corners. The hare’s dark fur contrasts the lighter part of the background, while the magpie’s pale abdomen and undertail contrast the darker portion of the background.

We hope that you have enjoyed this journey across eight of the greatest paintings in Chinese history and that you have developed a more profound insight into classical Chinese art.