"A goiter grows upon my neck as I stoop...

my stomach’s squashed under my chin.

My beard points to the sky, my back is bent like a bow...

the brush, constantly above my face, drips paint onto my features...

I see no line that I have drawn."

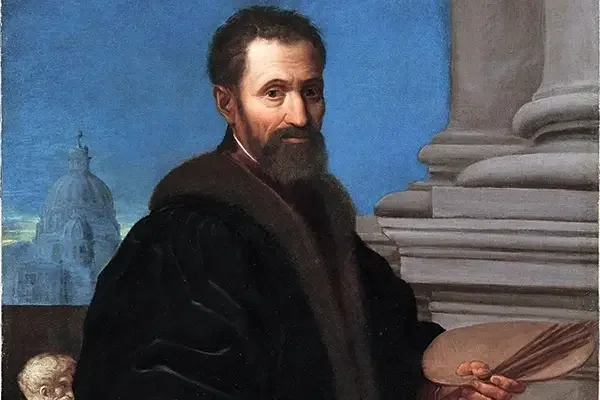

For four years, Michelangelo set aside his chisel and worked on a scaffold, painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel above him. With an aching back, burning eyes, and paint dripping onto his face, he created one of the greatest masterpieces in art history. Yet for him, the task was a burden. He was a sculptor, not a painter. He had tried in vain to convince the Pope that Raphael was better suited for the job. But Julius II would not be swayed. Michelangelo had no choice but to accept his duty—thus, he became a painter against his will. His resentment was clear in the way he signed his letters for the next four years: “Michelangelo, sculptor in Rome,” he wrote defiantly, despite having put down his chisel for so long.

And yet, despite his disdain for the task, Michelangelo did what he always did: he gave more than anyone expected of him. Where others might have compromised, he demanded perfection. His obsession tested the Pope’s patience. Julius II frequently asked when the work would finally be finished, and Michelangelo always gave the same answer: “When I can.”

He worked himself to exhaustion, taking little rest and often losing track of time. Meals were an afterthought—at times, he sustained himself on nothing more than a piece of bread. He rarely slept for long and often dozed off in his clothes, utterly consumed by his work. The pressure was immense, but his determination was greater.

But it had all begun so differently. At 14 years old, he entered the art school in the garden of Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence—a paradise for him. And when he first held a piece of marble and a sculptor’s chisel in his hands, it was as if he were witnessing the first day of creation. His first work, a faun figure, was sculpted with youthful enthusiasm. But the faun was smiling, revealing a set of strong teeth—an inconsistency in the eyes of Lorenzo the Magnificent:

"You have made this faun old, yet given him all his teeth. Don’t you know that old men always have one or two missing?"

Michelangelo did not need to be told twice. The very next day, a tooth—root and all—had been removed. Impressed by his determination, Lorenzo took the young artist into his palace.

What began as artistic freedom soon became a life dictated by obligations. Michelangelo was not the type to design from the safety of a studio. His work as a sculptor did not begin in his workshop but in the marble quarries of Carrara and Pietrasanta. He examined the stone himself, supervised the work of the stonemasons, helped lower the blocks, built roads for transport, and even chartered boats to ship the stone to Rome. At times, he wondered why he always started “at the roots of the tree”—he could have remained in Florence, sketching and calculating measurements. But no, he was always at the heart of the labor, ensuring that each piece of stone was already alive in his mind. Workers often laughed when he suddenly called out:

"Watch his feet!"

"Don’t injure his shoulders!"

"You clumsy devils! You’ve broken his nose!"

But Michelangelo was not one to quietly follow orders or accept mistreatment. He was headstrong, passionate, and unforgiving when it came to his art. In 1506, tensions between him and Pope Julius II reached a breaking point. Feeling wronged, Michelangelo left Rome in anger and fled to Florence. But the Pope would not let the matter rest—he even threatened war against the Florentines if they did not surrender Michelangelo. Under this pressure, a reconciliation was arranged in Bologna.

But Michelangelo never found peace. He was constantly given new commissions he could not refuse. The works closest to his heart were left unfinished. He longed to complete his sculptures, but princes, merchants, cardinals, and popes all demanded pieces from him. Everyone wanted a masterpiece, and so he moved from one colossal project to the next—often reluctantly.

After four years of labor, Michelangelo finally completed the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Yet he felt little satisfaction. In a letter to his father, he wrote briefly:

"I have finished painting the chapel. The Pope is extremely pleased. My other affairs are not going as planned or as I would wish."

The unfinished haunted him more than the completed ever fulfilled him. But Michelangelo understood the power of art and the talent behind it. Once, he said:

"He who masters this great art should know that he wields an incomparable power."

It was not fame or influence that made art powerful—it was the ability to bring life from stone, a gift that pushed Michelangelo to the very limits of his strength. And yet, the works he left behind are immortal—sculptures, frescoes, and architecture that still reach toward the heavens today.

B.

Comments · 2

Mindful Living

7 days ago