Have you ever wondered why Chinese holidays — such as the New Year, the Mid-Autumn Festival, and the Dragon Boat Festival — are celebrated on different dates each year, or why every year is represented by an animal from the Chinese zodiac? Or have you pondered what is the meaning behind the symbolic correspondences within this intricate yet fascinating calendar system?

This Jan. 22 marks the Chinese New Year, the year of the Water Rabbit. Let’s explore how the Chinese counted years in ancient times, and the remarkable way in which the traditional Chinese calendar was ordered to balance cosmological cycles.

In tune with the cosmos: the lunisolar calendar

The ancient Chinese were extraordinarily knowledgeable in several subjects, one of which was astronomy. They studied the celestial bodies, understood their cycles and examined their relationship to the biological cycles of life on Earth. Thus, their method of counting years and their way of adapting to changes in nature followed astronomical phenomena.

In the traditional Chinese calendar, the months are counted following the monthly cycles of the lunar phases, with each month beginning with the new moon. The length of a year is defined by the time it takes for the sun to return to the same position in our sky — known as solar terms — which, in turn, gives rise to the four seasons.

Since this system combines both the lunar calendar and the solar calendar, the traditional Chinese calendar is a lunisolar one. Were it only solar, like the Gregorian calendar, the months would be out of sync with the changes in the moon. Were it purely a lunar system, like the Islamic calendar, the years would fall out of sync with the earth’s orbit and the four seasons.

Leap months instead of leap days

The solar year is 365.2425 days long, which could be approximated to 365 ¼ days. Since it is not very practical to include just a quarter day every year, the Gregorian calendar keeps itself up to date by adding an additional day every four years — Feb. 29. The next leap year is 2024.

A similar concept is used to prevent the lunisolar calendar from drifting out of sync with the rotations of the earth around the sun. The ancient Chinese calculated that a lunar month is on average 0.92 days shorter than a solar month, which means that a 12-month-year using this system would be only 354 days long.

To compensate for this, the Chinese accumulated the days that were “missing” in each lunar month — with respect to the solar system — until these added up to between 29 to 30 days, that is, a full month. This would take between 32 to 33 months (approximately 3 years), at the end of which a 13th month would be added to the year.

A Chinese leap month (rùnyuè 閏月) — is added to the lunisolar calendar about once every three years, making it possible to keep the lunar and solar years aligned. Years with 12 months are known as common years (píng nián 平年) and those with 13 months are called long years or leap years (rùn nián 閏年).

The cycle is complex, using a broad range of astronomical calculations for perfect accuracy, but has its general rules. A lunisolar cycle lasts roughly 19 years, in which there are always seven leap years. A leap year is determined by finding the number of new moons between the 11th month in one year and the 11th month in the next.

If between the two “Chinese Novembers” (the 11th month) there are 13 new moons, that year must contain a leap month.

Leap months are added to a certain month and named after the month it follows. For example, in 2023, the second month will be doubled, and thus run 59 days from Feb. 20 in the Western calendar all the way to April 19.

Which month is to be doubled is normally determined by its relation to the 24 solar terms, which are introduced later in this article.

In keeping with changes in nature, the ancient Chinese named lunar months according to biological phenomena. Months also had correspondences with spiritual elements — namely yin and yang, and the Five Elements — that form the basis of the famous Chinese zodiac.

Solar terms and the start of the year

In the traditional Chinese calendar, years begin on the second new moon after the winter solstice in the northern hemisphere. This astronomical phenomenon is caused by the arctic pole reaching its maximum tilt away from the sun, and gives rise to the shortest day of the year, either on December 21 or 22 of the Gregorian calendar.

As each year began, the ancient Chinese closely followed the position of the sun in the sky, identifying the changes it dictated on nature throughout the year. As a result, twenty-four different solar terms were distinguished — each 15 or 16 days long — which made it possible to predict the arrival of the seasons and determine the right time to grow and harvest crops during the year.

With each solar year (Suì 歲) carefully calculated between winter solstices and accurately divided into 24 solar terms, the Chinese could not only synchronize their agricultural activities with the seasons, but also predict the celestial phenomena that would guide when to celebrate significant rituals and ceremonies in keeping with their moral duty to express reverence and respect for heaven and the divine.

Each solar term was also given its own name to denote the main changes it introduced in nature.

The 48th century

Chinese people refer to the traditional calendar as the lunar calendar (陰曆) or “farmer’s calendar” (Nóng lì 農曆), with the latter name being encouraged particularly after the communist takeover to remove its spiritual and upper-class connotations. But the calendar should properly be known as Huang li (黃曆) — the Calendar of the Yellow Emperor.

According to legend, the Yellow Emperor, or Xuanyuan (軒轅黃帝), was the founder of Chinese civilization who united the tribes living along the Yellow River and pacified barbarian forces with weapons and magic granted to him by the gods.

Throughout history, Chinese usually referred to the year by its position in the 60-year zodiac cycle, or by the regal year of whichever emperor was on the throne.

But out of respect for the Yellow Emperor, the Chinese calendar begins with the year of his reign nearly 5,000 years ago in 2698 B.C. That makes 2023 Year 4721 by the Chinese reckoning.

The sexagenary cycle and the Chinese zodiac

In addition to calculating the length of celestial and terrestrial cycles, the ancient Chinese developed a deep understanding of the relationship between cosmic time, natural elements and human life.

They created a system for identifying years, months and dates, by incorporating the fundamental philosophies of the Yin and Yang, the Five Elements, the Chinese Zodiac and Chinese astrology.

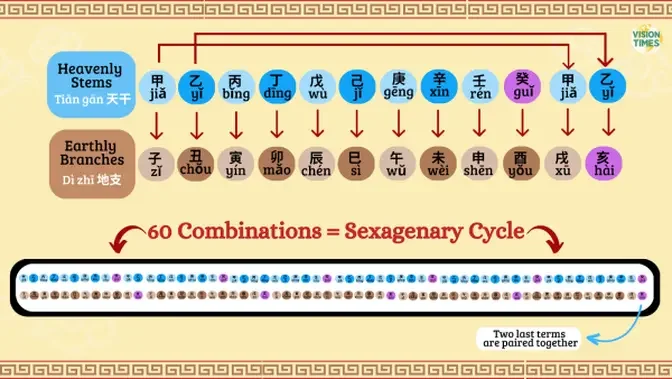

This system is called the “Sexagenary Cycle” or “Stems-and-Branches” (Gānzhī 干支) and it encompasses 60 terms to denote units of time. Its use goes back thousands of years, serving not only as a tool for measuring time, but also for predicting the fate of an individual or an entire society. Let’s take a look at how this system works.

The Stems-and-Branches system is based on 10 Heavenly Stems (Tiān gān 天干) and 12 Earthly Branches (Dì zhī 地支), all arranged in a set order. These are:

Heavenly stems: 甲乙丙丁戊己庚辛壬癸

Earthly Branches: 子丑寅卯辰巳午未申酉戌亥

The two systems are combined to create unique pairs, each consisting of a stem and a branch. The combination is made following their predetermined order, pairing the first stem with the first branch, the second stem with the second branch and so on.

This gives us the first 10 terms of the 60-term cycle:

- 甲 子

- 乙 丑

- 丙 寅

- 丁 卯

- 戊 辰

- 己 巳

- 庚 午

- 辛 未

- 壬 申

- 癸 酉

Since there are more branches than stems, the last two branches are paired with the first two stems, and the elements of both systems are continuously listed until the last elements of each system — that is (guǐ 癸) and (hài 亥) — come together, leaving no element unpaired. This combination gives rise to 60 unique stem-branch pairs:

These ordered pairs are used to count years in the traditional Chinese calendar with the cycle repeating every 60 years. Using this system, 2023 starting Jan. 22 will be the the year 癸卯 (guǐ mǎo), the 40th year of the current sexagenary cycle. It follows that the last 癸卯 (guǐ mǎo) year was 1963, exactly 60 years ago.

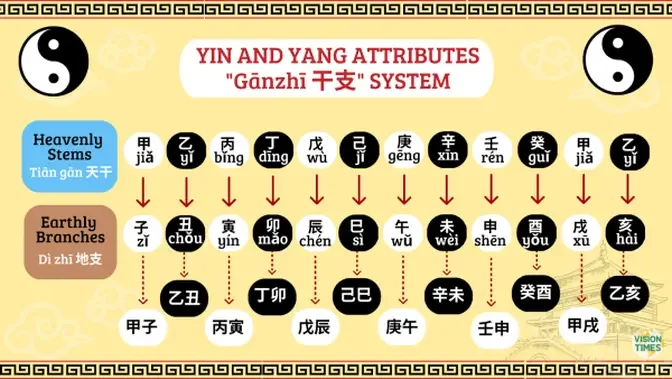

Alternations of yin and yang

According to the Chinese, each stem and branch has an attribute of either yin or yang, the dual forces described in Daoism. Those occupying even positions in their systems are yin — usually represented in black — and those in odd positions are yang — denoted in white.

By symmetry, each pair of stems and branches of the sexagenary cycle is composed of elements having the same attribute, which in turn defines the overall yin or yang nature of its corresponding year.

An easy rule of thumb to discern if a year in the Gregorian calendar is yin or yang, is that years that end in an even number are yang while those that end in an odd number are yin. This means that the year 2023, starting on January 22 according to the Chinese calendar, will have the yin attribute.

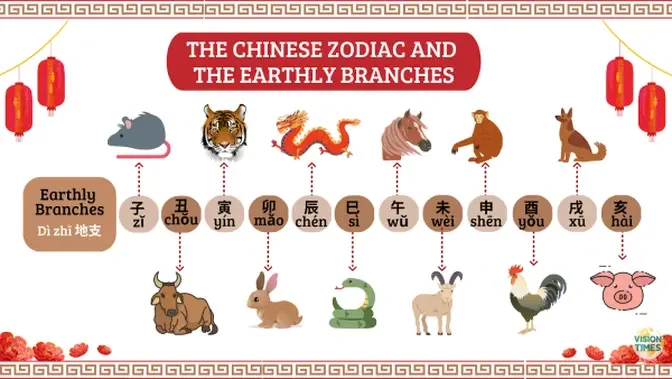

Animals of the Chinese zodiac

The Chinese zodiac is a series of twelve animals that were assigned to the twelve earthly branches. Since each earthly branch is associated with a specific animal, each year of the sexagenary system corresponds to a zodiac animal in a cycle that repeats every 12 years.

In order, the zodiac animals and their associated branches are:

子: Rat, 丑: Ox, 寅: Tiger, 卯: Rabbit, 辰: Dragon, 巳: Snake, 午: Horse, 未: Goat, 申: Monkey, 酉: Rooster, 戌: Dog, and 亥: Pig.

Since each animal will always correspond to a particular branch, we can infer that each zodiac animal will always be accompanied by a fixed yin or yang property. As such, all Rat years will have Yang attributes, while Ox years will have yin attributes.

By this point we may be able to understand why the year 2022 is said to be the year 壬寅 (rén yín) of the sexagenary cycle, with the Tiger as its zodiac animal and yang as its primary nature. It follows that 2023 will mark the beginning of the year 癸卯 (guǐ mǎo) with the Rabbit as its zodiac animal and yin as its predominant attribute.

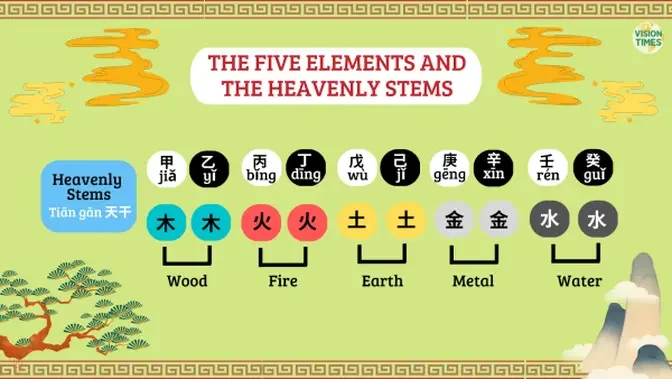

The five elements

The ancient Chinese believed in the harmony between man and nature. Thus, the traditional Chinese calendar includes the philosophy of the Five Elements (wu xing 五行) — metal, wood, water, fire and earth — the phases believed to constitute all things in the world.

Similar to how zodiac animals correspond to the twelve earthly branches, we can think of the five elements corresponding to the ten heavenly stems. The exact divisibility of the number of stems — ten — by the number of elements — five — results in a perfect correlation that allows all elements to manifest an equal number of times during the 60-year cycle, while exhibiting both yin and yang nature.

The five elements are assigned to heavenly stems following the order of their generation, that is: wood (木 mù), fire (火 huǒ), earth (土 tǔ), metal (金 jīn), and water (水 shuǐ).

Depending on the heavenly stem of any given year in the sexagenary system, the corresponding element properties will be attributed to it. For instance, any year starting with 甲(jiǎ), such as the year 1974 which was 甲寅 (jiǎ yín), will have the properties of wood. Likewise, any year starting with 丙 (bǐng), such as the year 1976 which was 丙辰 (bǐng chén), will have the properties of fire.

Since each element is assigned to two consecutive heavenly stems, all elements receive a yin attribute and a yang attribute. This way we can say that the first heavenly stem 甲(jiǎ) corresponds to yang wood while the second heavenly stem 乙 (yǐ) represents yin wood. Likewise, the fifth heavenly stem 戊 (wù) corresponds to yang earth while the sixth stem 己 (jǐ) represents yin earth.

Applying this to our current cycle, we get that the year 2022 (壬寅) corresponded to Yang water and that the new year in 2023 (癸卯) will represent yin water. More properly, we would say that 2022 was the year of the yang Water Tiger and that 2023 will be the year of the yin Water Rabbit.

Following the combinations of the sexagenary cycle, we can infer that while each zodiac animal has a fixed yin or yang nature — for instance, the tiger is always yang and the rabbit is always yin — they will all come to have the properties of each of the Five Elements. Thus, we will have years corresponding to the Wood Horse, Fire Horse, Earth Horse, Metal Horse and Water Horse; all of them with yang attributes.